Photo: Public Health Agency of Canada

MONTREAL – When a 50-year-old Quebec woman was sentenced to 10 months in jail and three years probation for assaulting police officers by spitting on them, her punishment sent a chill among anyone living with HIV.

A Maniwaki judge ruled last year that the woman, who was positive for human immunodeficiency virus, had caused the two arresting officers extreme anxiety when she spit on them.

Never mind that it’s been known for many years that HIV, like hepatitis C, cannot be transmitted through saliva.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there is no documented case of transmission from an HIV-infected person spitting on police or anyone else.

But one officer claimed that after the incident she was afraid of passing an infection to her baby, while the other officer said he was unable to go back to work because he was suffering side-effects from taking anti-viral drugs as a precaution against HIV infection.

During sentencing, the judge said that the courts must send a clear “unequivocal signal” that spitting on citizens will not be tolerated by people with HIV or hepatitis C.

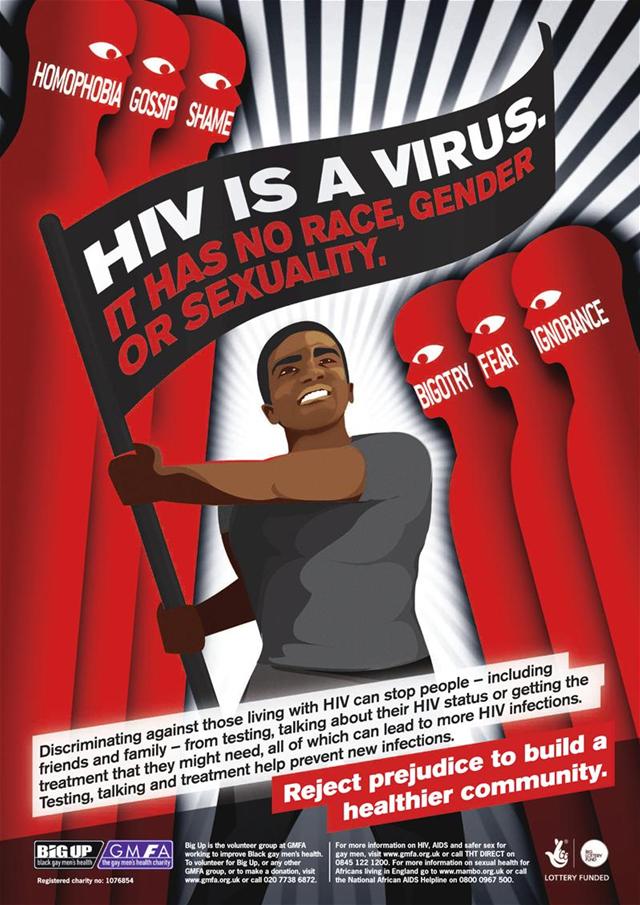

The case is a striking example of the legal consequences of HIV/AIDS discrimination and stigma, said lawyer Liz Lacharpagne of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. “Spitting is an assault but most people are not sent to jail for that,” she said. “She got an enormous sentence because they were afraid of HIV.”

The face of HIV/AIDS has changed dramatically in Canada over the past two decades, turning into several epidemics in different population groups, according to Health Canada. Men who have sex with men remain the group that’s most affected by HIV/AIDS, but the disease has also become a public health issue for injecting drug users, women, Aboriginal peoples, prison inmates, immigrants from countries where HIV is endemic, as well as those already living with HIV/AIDS. And studies show “a significant potential” for of HIV transmission among youth.

A diagnosis is no longer a death sentence. People newly diagnosed with are told to go back to work — to keep their dreams and to expect to live as long as anyone else with a chronic illness. Highly effective retroviral drugs have reduced HIV to undetectable levels in semen, vaginal fluids and blood.

One thing hasn’t changed, say AIDS activists, and that is the fear that disclosing a health status of HIV infection will lead to negative consequences. On top of handling health conditions, people living with AIDS have reported facing rejection by family and friends, job refusals and home loss, and some became victims of violence.

“Criminalization” is now part the changing portrait of AIDS, said Lacharpagne, who works as legal counsel for COCQ-SIDA, a coalition of Quebec community organizations involved in the fight against AIDS.

The organization has seen an increase in discrimination complaints since the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on Oct. 5, 2012 that people living with HIV have a legal duty to tell their sexual partners about their HIV infection, except when the risk of transmission would be close to zero — a condom has to used and the person’s viral load must be so low as to be undetectable.

Source: Positive Living Society